Fortunato Depero, Riso cinico, 1915

Fortunato Depero (1892-1960) was born in Fondo in Trentino when this northeast corner of Italy belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was never one of Futurism's leading members, but he was the most persistent, the man whose work embodied many of the movement's best inclinations (combining disparate art forms) and worst prejudices (glorifying Fascism). Following a traditional craftsman's training, Depero was rejected by the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, ending up back in Fondo as a marble cutter's apprentice. And it's there that he might have settled, carving mausoleums for Austrians, had he not heard the distant call to "sing to the love of danger" (as the founding Futurist manifesto proclaimed) and create a genuinely new, militantly Italian culture.

Fortunato Depero, Il ciclista attraversa la città, 1945

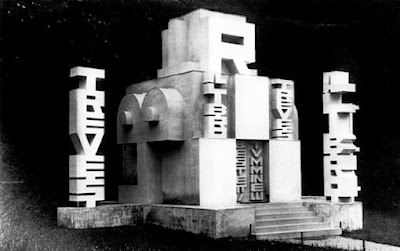

After his mother's death in 1914, Depero moved to Rome, where he sought out one of Futurism's leading talents, Giacomo Balla, who immediately saw Depero's potential. It was with Balla in 1915 that he wrote the manifesto Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo (Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe). In 1919, Depero founded the Casa d'Arte Futurista (House of Futurist Art) in Rovereto, which specialised in producing toys, tapestries and furniture in the futurist style. In 1925, he represented the Italian futurists at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. The freedom with which he moved between media over the course of his five-decade career made him Futurism's common denominator. One of his masterpieces wouldn't be in painting but in architecture, specifically the pavilion for the 1927 Monza Biennale Internazionale delle Arti Decorative that had an immaculate white facade and larger-than-life block letters for walls:

Fortunato Depero, Pavilion for the Monza Biennale Internazionale delle Arti Decorative, 1927

As his pavilion proved, the erstwhile marble cutter had the brute ingenuity that Futurism prized as its most potent weapon against "passéist" complacency. Marinetti had recognized that from the day they met in 1915, inside Depero's studio on Rome's Via Cola di Rienzo. Depero showed Marinetti stacks of paintings, as well as machines built of cardboard. There were also his "abstract" poems written in colored inks on large polychrome sheets dangling from the ceiling. Marinetti read some of these aloud, recognizing his own influence: For several years, he'd been leading a revolt against adjectives, adverbs, and conjunctions, promoting what he called "words-in-freedom", a typographic onslaught to directly transcribe modern-world experience. For instance, he set the sounds of battle in verse with declamations such as zang-tooooomb-toomb-toomb and pacpacpicpampampac. By 1916, Depero had taken the concept to a new extreme with "onomalingua," a mechanical dialect (vroiii sioiii oiii) in which he claimed to converse directly with automobiles and trains.

Fortunato Depero, Grattacieli a tunnel, 1930

However, it was Depero's assemblages in cardboard - with geometric flowers stiff and artificial, such as might bloom in a robotic garden - that changed the course of his career. When he saw them, Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, declared Depero "the new Rousseau". Diaghilev commissioned him to create Futurist scenery and costumes for Stravinsky's ballet, Song of the Nightingale. Decades ahead of their time, Depero's experiments in mechanized movement were never to reach the stage. Stravinsky's ballet was delayed and reworked and ultimately staged years later with a set by Henri Matisse.

Fortunato Depero, The Chair's Party (tapestry), 1927

In 1925, Depero produced a gruesome tapestry, War=Festival showing soldiers slaughtering one another against a backdrop resembling a jubilant pyrotechnic display. Though morally appalling, it was a magnificent example of artistic propaganda - visually alluring enough to win a gold medal at that year's Paris International Exhibition of Decorative Arts. His Fascist political allegiance was duly forgiven by his countrymen following his vague post-war acknowledgment of "those human and justifiable mistakes committed in good faith."

Fortunato Depero, Martinetti, Patriotic Storm, 1924

Depero's compositional spareness led the way to the bold ads, posters and bottle designs he produced over the following decades for companies like Campari and San Pellegrino. In 1927, Depero published a personal portfolio, titled Depero Futurista (shown below). Bound with two large industrial bolts, the book included some of the potent graphics he had designed for Campari, interspersed with anarchic flights of typography that were essentially advertisements for himself.

Fortunato Depero, Campari Soda Bottle Design, 1932

In 1928, Depero moved to New York, where he produced costumes for stage productions and designed covers for magazines including Movie Maker, The New Yorker and Vogue. He also was active in interior working on two restaurants (which were later demolished to make way for the Rockefeller Center), did work for the New York Daily News and Macy's, and built a house on West 23rd Street. In 1930, Depero returned to Italy.

Fortunato Depero, Depero Futurista, 1927

In the 1930s and 40, due to futurism being linked with fascism, the movement started to wane. One of the projects Depero was involved in during this time was Dinamo magazine, which he founded and directed. After the end of the Second World War, Depero moved again to New York. One of his achievements on his second stay in the United States was the publication of So I Think, So I Paint, a translation of his autobiography initially released in 1940. Between 1947 and 1949 Depero lived in a cottage in New Milford, Connecticut, working on his long-standing plans to open a museum. His host was William Hillman, an associate of then President Harry S. Truman.

Fortunato Depero, Table and Chair, 1962

In 1949, Depero returned to Rovereto, where he died in 1960. In 1959, Galleria Museo Depero opened, fulfilling one of his long-term ambitions. It is a division of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto, Italy's only museum dedicated to the Futurist movement, containing more than 3.000 objects.

No comments:

Post a Comment